Sun Tzu: Aversion to War

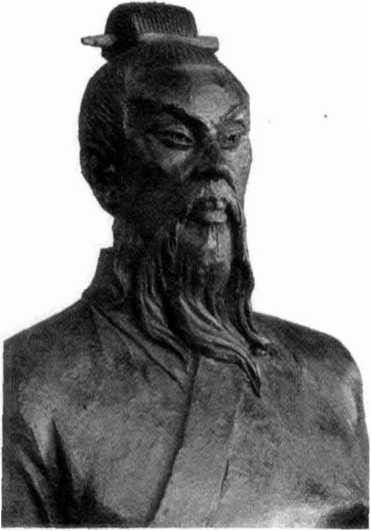

Sun Tzu (sunzǐ, 孙子) (aka Sun Wu) was born in the State of Qi (in the area of modern Shandong Province) as a contemporary of Confucius (551-479 BCE) during the late Spring and Autumn Period. He fled with his family to the State of Wu (Wu), when the province of Qi was in chaos. He assisted He Liyu (r. 514-496 BC) as a military leader and defeated the state of Chu several times. Sun Wu wrote The Art of War in thirteen chapters.

The basic tenet of the Art of War is a fundamental aversion to war. War should only be fought when there is no alternative. For Sun Tzu, war is a vital issue of state. It is the field of life and death, the road that leads to either survival or destruction, and so it must be explored with extreme caution. State leaders must be extremely wary of war unless there are no other alternatives. Even a military victory is a defeat in the sense that it requires the expenditure of the state’s human and material resources. For Sun Tzu, the most important factor in resolving a conflict between states is the strategy of attack. “The best military policy is the strategy of attack; the next is to attack alliances; the next is to attack soldiers; and the worst is to attack walled cities.” Thus, the highest level of the art of war is to force the enemy to abandon the attack.

Once one goes to war, one must control the entire situation, control others without being controlled by others. One must adapt to the changing situations on the battlefield. This requires sensitivity and adaptability with the intuitive ability of a genius. One wrong idea can lead to the death of many soldiers. A general must control the situation with the absolute authority of a commander and remain at ease in the face of changes on the battlefield. The changing situation on the battlefield requires a commander to have strong self-control. As a commander, he must not have any personal interests. He can only respond objectively to changing situations. Only in this way can a great general take full advantage of circumstances and achieve his goal. Therefore, for a great general to be able to make correct decisions, he must have an outstanding character, a peaceful mind, and extremely accurate judgment.

There are five criteria that determine the outcome of a war: the route, the climate, the terrain, the command, and the law. To judge the outcome of a war, the following situations must be assessed: How aligned are the people's thinking with their superiors? What is the climate or the seasons? Are there any advantages in terrain on our side? How do the commanders relate? Does the law lead to organizational efficiency? The possibility of winning a war must be judged by many aspects. These are called the "five criteria (ears, wushi " (Laughs)".

It is important to assess the situation from both sides and analyze it in detail. It is imperative to be fully prepared before entering a war. The possibility of winning a war depends on the circumstances and the method of preparation. Sun Tzu points out that "he who knows the enemy and himself will never be at risk in a hundred battles." One of the key methods of knowing your enemy is the use of spies. Only through accurate reconnaissance can you have confident control over the battlefield.

Great Teaching (Daxue), Middle and Unchanging (Zhongyong) and the four chapters of Guanzi develop the theme of self-improvement in pre-Qin political philosophy. The Great Learning was originally a chapter of the Book of Rites (Liji). It is said that it was written by a master. Zeng, a disciple of Confucius. The "Great Learning" is a teaching on how to be a "highly moral person" (dazhen, dare 大人), which now means "adult" in Chinese. It also means cultivating oneself to become a "great man" (a model person/sage). Traditionally, this was seen as learning to achieve a state of "perfect wisdom and virtue (nation

vayvanIn pre-Qin political philosophy, the process of cultivating the heart-mind-body-family-state in the Great Teaching provides a practical model for later Confucians.

Unlike Daxue, Zhongyun provides a working model for a person to face a fundamental real situation. This basis for worry and anxiety (jieshen) resembles the Confucian model of political education. Confucius does not discuss tian in detail, but Zhongyun gives the mandate from heaven as the basis for Confucian political education. In the "Judgements" Confucius does not mention the Tao of heaven and does not create a solid ontological basis for his political education. But Zhongyun, written Zisi, the grandson of Confucius, lays a fairly solid foundation, which is the mandate of heaven (tianming), mirroring the model of Confucian political education.

In Guanzi there are four chapters entitled "the mechanism of the heart-mind" (Xinshu, two chapters), “cleansing the heart-mind (baixin)" and "the art of functioning of the inner mind (Naye)". These four chapters focus on being "empty, centered, peaceful, and adaptable". They explain the art of operating one's mind to enlighten and control the world. This is achieved by incorporating pre-Qin political philosophy into personal self-cultivation and the continuity of personal qi-cosmology into the qi of the entire universe.

Translation: Alexey Karpov

Original: Chinese Philosophy by Wen Haiming (pp. 59-62)