Guangxingtai Observatory: Time was counted here

My name is Alexey Karpov, and I am standing in Gaocheng Township (高城, Gāochéng), Dengfeng City (登封, Dēngfēng), Henan Province (河南, Hénán), at the ancient Guangxingtai Observatory (观星台, Guānxīngtái). This place, known as the “middle of the world” (天地之中, Tiāndì zhī zhōng), is not just a dot on the map, but the heart of China (中国, Zhōngguó), where more than three thousand years ago astronomical discoveries were born that changed the world. Here, among the ancient stones and shadows, I feel history come alive and the stars whisper their secrets. I will tell you why Guangxingtai is a must-visit for anyone who wants to understand the soul of China.

Zhou Gong and the Birth of Astronomy

Behind me is the Shadow Measuring Platform of Emperor Zhou (周公测影台, Zhōugōng cè yǐng tái), a Tang Dynasty (唐朝, Táng cháo) structure dedicated to Emperor Zhou (周公, Zhōugōng). This prominent Zhou Dynasty (周朝, Zhōu cháo, 1046–256 BC) statesman used a simple instrument, the earth gnomon (土圭, Tǔguī), to measure shadows cast by a wooden pole more than three thousand years ago.

His goal was ambitious:

determine the astronomical data for moving the eastern capital to Luoyang (洛阳, Luòyáng)

Zhou Gong spent years observing shadows, noting their length. He identified key moments of the year:

- Summer Solstice (夏至, Xiàzhì): shortest shadow, longest day.

- Winter Solstice (冬至, Dōngzhì): longest shadow, shortest day.

- Spring Equinox (春分, Chūnfēn) And Autumnal Equinox (秋分, Qiūfēn): equal length of day and night.

These observations formed the basis of the 24 Seasons System (二十四节气, Èrshísì jiéqì), which became a cornerstone of Chinese culture. The system did more than simply divide the year into 24 periods; it also synchronized people’s lives with the rhythms of nature, from the sowing of rice in the spring to the harvest in the fall. Each season, whether “Beginning of Spring” (立春, Lìchūn) or “Little Snow” (小雪, Xiǎoxuě), was associated with agricultural work, rituals, and even poetry. Standing here in Dengfeng, I can imagine farmers thousands of years ago aligning their actions with these cycles, and emperors performing ceremonies to please the heavens. This harmony with nature is what makes Chinese civilization unique, and it all began with the simple shadows measured by Zhou Gong.

In 2016, the system of 24 solar terms was included in the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage, and it’s no wonder. It not only demonstrates the astronomical precision of the ancient Chinese, but also reflects the philosophy of the unity of man and the cosmos. Guangxingtai, where this knowledge was born, has become a symbol of this heritage. Walking by the platform, I see tourists from different countries taking pictures of the “celestial ruler” and listening to the guide tell about Guo Shoujing. This place unites people, reminding us that the desire to understand the stars is universal. For me, as a traveler, it is also a reason to be proud of the fact that I am standing where this world history began.

It is here in Dengfeng, where Emperor Zhou declared the place to be the “center of the world” (天地之中, Tiāndì zhī zhōng), that I realize that every stone beneath my feet holds the memory of great discoveries, and the stars above seem the same as Emperor Zhou saw them three thousand years ago. This place is not just a point on the map, but the center where earth and sky, past and future, meet. I close my eyes and feel part of this eternal history, where man first attempted to measure the universe.

Unique fact: The transfer of the capital to Luoyang required not only practical calculations, but also a philosophical justification. Zhou Gong used the idea of the "middle of the world" as a symbol of harmony and the legitimacy of power. This concept, expressed in the principle of "the king should be in the center" (王者居中, Wáng zhě jū zhōng), became the basis of Chinese political and cultural thought.

Metaphysics

In my Bazi practice, the 24 seasons are not just seasons like summer, but the pulse of the universe that sets the rhythm of human destiny. Each season, from the “Beginning of Spring” (立春, Lìchūn) to the “Great Cold” (大寒, Dàhán), carries its own energy (qi) that influences the natal chart. For example, being born during the “Grain Rain” (谷雨, Gǔyǔ) period can strengthen the Water element, while “White Dew” (白露, Báilù) adds subtlety to Metal. When I review my Bazi in the morning, I always consult these beats to understand how the celestial cycles are shaping my path.

Here, I see the origins of this wisdom—the place where man first synchronized his life with the breath of the cosmos. Guangxingtai reminds me that these terms were born from observing shadows and stars. Walking on the ancient platform, I imagine Zhou Gong looking to the sky to understand how the energy of the earth and sky affected life. This place teaches me that feng shui is not just about arranging furniture, but the art of living in harmony with the cycles of nature.

"The Middle of the World" and the character "Zhong"

The character "zhong" (中, Zhōng), meaning "center" or "middle," permeates Chinese culture. It appears in the words:

- China (中国, Zhōngguó) - "Central State".

- Chinese (中华, Zhōnghuá) - "Central Civilization".

- Central Plains (中原, Zhōngyuán) — the historical core of China.

- Middle of the World (天地之中, Tiāndì zhī zhōng) — the philosophical center of the universe.

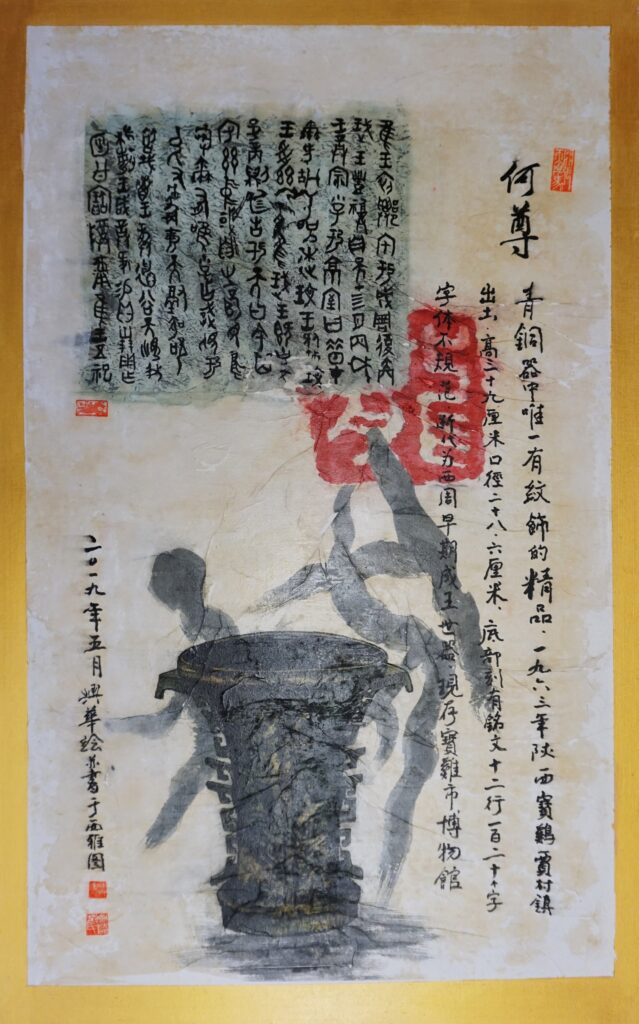

The Chinese character for China first appeared on the Hezun (何尊, Hé zūn) bronze vessel found in Baoji (宝鸡, Bǎojī), Shaanxi Province (陕西, Shǎnxī). The inscription on the vessel mentions moving the capital to the “middle of the world” — all related to Zhou Gong’s measurements.

Did you know?, that the word "zhong" in Henan can also mean agreement? According to local legend, thousands of years ago, elders would gather on the plains of Henan to fairly divide the lands between clans. Using a gnomon, they would locate the center point, draw a line, and ask each other, "Zhong bu zhong?" (中不中?, Zhōng bù zhōng?), meaning "Is this the middle? Is it right?" The phrase, according to folklore, originated in Dengfeng, where Emperor Zhou declared Henan to be the "middle of the world."

Guangxingtai: An Observatory Ahead of Its Time

To the north of the Zhougong platform stands the Guangxingtai Observatory (观星台, Guānxīngtái), built in 1276 during the Yuan Dynasty (元朝, Yuán cháo) by the eminent astronomer Guo Shoujing (郭守敬, Guō Shǒujìng). He modernized the Zhougong platform by creating a 12.62-meter-tall brick structure known as a guibiao (圭表, Guībiǎo). Guo Shoujing established a network of 27 observatories across China, but Guangxingtai in Dengfeng was the central one—and the only one that survives to this day.

Beside me is the “heavenly ruler” (量天尺, Liángtiān chǐ) that Guo Shoujing used to measure shadows to determine the 24 solar cycles. His work led to the Shòushí lì calendar, which defined the length of a year as 365.2425 days—just 26 seconds off the modern estimate of the tropical year. Developed in the 13th century, this calendar predated the Gregorian calendar, adopted in Europe in 1582, by 300 years. Standing here, I marvel at how Chinese scholars, armed with nothing more than shadows and rulers, achieved such precision.

Architecture and traces of history

Guangxingtai is not only a scientific structure, but also a witness to history. On the eastern wall (can you imagine, I didn’t take a photo of this) you can see two traces of Japanese artillery shelling in 1944 – a reminder of the turbulent times of the 20th century. Opposite the entrance to the complex there is a zhaobi wall (照壁, Zhàobì) with an inscription from the Qing Dynasty (清朝, Qīng cháo), made during the reign of Emperor Qianlong (乾隆, Qiánlóng): “Qian gu zhong chuan” (千古中传, Qiāngǔ zhōng chuán), which is translated as “transfer of the center through millennia”. These words seem to say: Guangxingtai is a bridge between the past and the future.

Guangxingtai's architecture is simple but functional. The brick platform and "sky ruler" create ideal conditions for measurements, and its location in the center of the Henan plains minimizes distortion from mountain shadows. This place is an example of how genius meets practicality.

Why Guangxingtai is a place for inspiration?

Visiting Guangxingtai is not just a tour, but a profound experience that inspires and teaches:

- Strategic Thinking: Zhou Gong and Guo Shoujing show how patience and careful calculations lead to great results. It is a lesson for leaders making decisions under uncertainty.

- Cultural immersion: Guangxingtai reveals why China considers itself the "middle of the world" and helps us understand its philosophy.

- Metaphysical connection: For practitioners of Bazi, Feng Shui and Qi Men, Guangxingtai is a source of energy, a place where, in a sense, 24 seasons, 10 heavenly stems and 12 earthly branches appeared for us. Strengthens intuition and connection with the Qi of the cosmos.

- Relaxation and inspiration: Dengfeng's tranquil atmosphere and views of the Songshan Mountains (嵩山, Sōngshān) are the perfect way to reset.

- Exclusivity: This is a place where you will feel like a part of ancient history, inaccessible to the mass tourist.

My advice: Combine a visit to Guangxingtai with a trip to the Shaolin Temple (少林寺, Shàolínsì), just 15 km away. A morning tour of the observatory and an afternoon kung fu or meditation class at Shaolin are the perfect balance for the busy executive looking for balance.

How to organize a trip

Route planning

- How to get there: Fly to Zhengzhou (郑州, Zhèngzhōu), the capital of Henan, then take a taxi (70 minutes) to Dengfeng. From Dengfeng, it's a 15-minute taxi ride to Guangxingtai.

- The best time: April-May or September-October - comfortable weather and picturesque views.

- What to take: Comfortable shoes and the best Guide

Additional activities

- Explore the Songshan Mountains (嵩山, Sōngshān), part of a UNESCO Geopark.

- Visit the temple Sanhuangzhai.

- Try local Henan cuisine such as hotpot noodles (烩面, Huìmiàn) or a tea ceremony in Dengfeng.

Conclusion

The Guangxingtai Observatory and the Zhougong Platform in Dengfeng are not just historical monuments, but symbols of humanity's quest for space exploration and harmony with nature. From the astronomical discoveries of Zhougong, who proclaimed Dengfeng to be the "middle of the world," to the calendar of Guo Shoujing, which was ahead of its time, these places embody the spirit of China as a center of civilization. For scientists, top managers, and metaphysicians, this is an opportunity to be inspired, rethink their goals, and touch the soul of China.

Plan your trip to Henan today and let Guangxingtai become your window to the heart of China!